Photography: Christian van Houwelingen, 2023

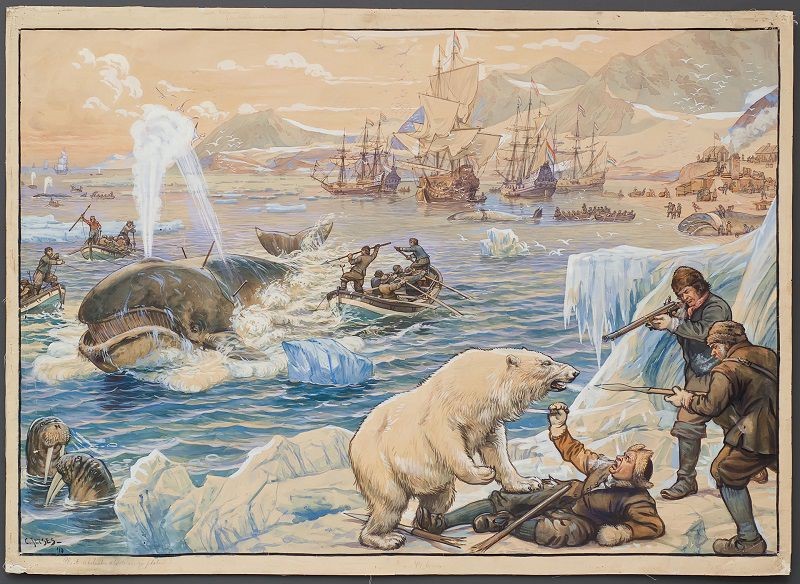

The striking 1911 school wall chart Ter walvischvaart [On Whaling] was designed to give Dutch schoolchildren an idea of the entrepreneurial and mercantile spirit of their ancestors in the first half of the 17th century. But this image had a very different effect on pupils, as museum staff at the Nationaal Onderwijsmuseum [National Museum of Education] in the Netherlands discovered during an exhibition on its creator, the educational illustrator Cornelis Jetses (1873-1955).

On Whaling is an iconic school wall chart. In many Dutch classroom photos from the period 1911-1975, this poignant image hangs on the wall. Generations of children have looked at it and been taught about it. The well-known journalist Henk Hofland (1927-2016), after visiting the Museum of Education, described what happened to him when he entered the room where the original watercolour was hanging: “I looked at this picture […] and at the same moment I was back in primary school, maybe for a minute, which is quite long for my age. […] I was back at the hand of the animals, just like when I was six or seven years old.”

Hofland was 81 when he visited the exhibition Jetses on the Wall (2009). What struck him as an “old man”, and made him shudder as a young boy, were the atrocities against mammals depicted in the painting. The polar bear is shot while a sailor shoves a lance down its throat. Barbed harpoons have been shot into the torso of the struggling whale.

© Nationaal Onderwijsmuseum, Dordrecht | Noordhoff Collection | H165.962

Hofland’s school memory has also been described by psychologists as a reminiscence experience: looking at Jetses’s school wall chart brought him into direct contact with his own distant childhood past. It was as if he were back in school for a moment. What the teacher was saying with this picture, the learning objectives, did not come to the surface. As an old man, he realised that Jetses, whom he calls an “enlightened spirit”, had sided with the animals in his painting. According to Hofland, Jetses did this consciously. This “scene of the highest dramatic order” awakened in him a lifelong love of animals.

Did the educational illustrator Jetses really deliberately side with the animals? I doubt it.

The spirit of trade

The teacher’s guide to this wall chart tells a different story. On Whaling would be an appropriate tool to give children an impression of the proverbial entrepreneurial and trading spirit of the Dutch in the first half of the 17th century. It was all about making money. It explains in detail how the Dutch whaling company recruited skilled harpooners from the Basque country and made gold from the cruel hunting of whales, as well as polar bears, walruses and foxes.

Monstrous

The manual for this wall chart describes at length the agony of a giant whale, “a monstrous animal”. The whale, wounded by a harpoon, is exhausted from loss of blood and can no longer dive: “By the mixing of the blood with the vapour rays it can be seen that it has been struck in the lungs.” With his last efforts, “the monster” smashes one of the sloops carrying the harpooners. The castaways are rescued. “Soon the whale’s hitting became weaker and he died of exhaustion and loss of blood.”

There is no animal-love here: the whale is described as a monster, and Jetses drew the polar bear with a ferocious expression. It was all about fox and polar bear skins, whale oil (used for lamp oil and soap), not to mention whale baleen (used, among other things, for hoop skirts and corsets in the fashion industry).

Generations of primary school children were horrified by On Whaling. The learning objectives were not met because the imminent death was realistically close on this image. But for some children, it has been the inspiration for an unconditional love for animals.