Animals, The North, and settler-colonialism in historical educational media:

A comparison of Dutch and Canadian sources in the early 1900s

By Pia Russell with Chaa’winisaks[1]

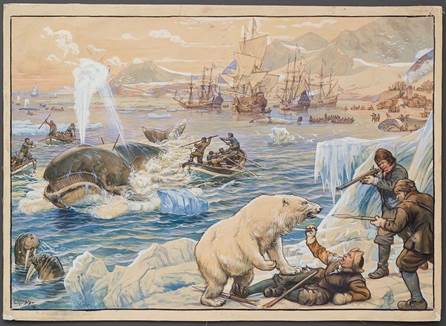

In November 2024, Jacques Dane, my INEHC colleague from the Nationaal Onderwijsmuseum [National Museum of Education] in the Netherlands wrote an excellent blog post titled ‘Animal love in the classroom.’ In this engaging piece, Jacques analysed an influential wall chart created in 1911 by Dutch educational illustrator Cornelis Jetses titled Ter walvischvaart [On Whaling]. Jetses’ Ter walvischvaart adventurously demonstrated to schoolchildren how important the Arctic was to seventeenth-century global economies in historical conceptions of the Dutch mercantile ethos. Through moving oral histories, Jacques described how iconic the wall chart was in Dutch schoolrooms for the next sixty years. Clearly the appeal of ‘Animals’ and ‘The North’ endured across generations of school children in the Netherlands and this was no less true in the history of Canadian schools as well.

(British Columbia edition). (1899). W.J. Gage & Co., Ltd. https://archive.org/details/newcanadiangeogr0000onta/mode/1up?view=theater

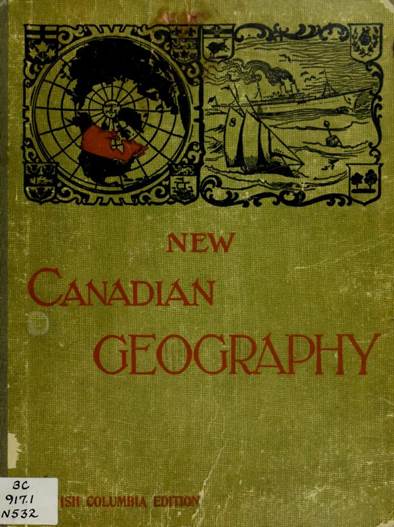

The New Canadian Geography textbook

Jetses’ Ter walvischvaart reminded me of a similarly themed and concurrent series of images from a Canadian textbook first published in 1899 titled New Canadian Geography: Specially adapted for use in public and high schools.[2] Published in Toronto by W. J. Gage & Company Limited with no individually attributed authors, this combined geography textbook and atlas was prescribed for wide use throughout British Columbian public schools from 1900 to 1912. The book’s title page also stated: “Authorized by the Board of Education for the use in Schools of…” and then the following provinces were listed—New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Quebec, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia.”[3] Clearly the New Canadian Geography was a textbook with considerable pedagogical and cultural influence across Canada during the first decades of the twentieth-century. Furthermore, it would have undoubtedly lingered on the shelves of school classrooms and libraries long after the period of curricular prescription was superseded.

Even a quick perusing through the well-worn pages of the New Canadian Geography shows a prioritization for the image over text as a pedagogical tool. When considered alongside Jacques’ observations of Jetses’ Ter walvischvaart, we see a comparable approach as utilized by wall charts of the same period. Doubly impactful too are both sources’ strong dependence on the motif of animals to convey educational content with the aim of fostering a persistent emotional appeal for children. Then, as now, youth audiences were regularly drawn into visual and textual narratives featuring animals. A close reading of an animal-focused section in the New Canadian Geography textbook reveals intriguing comparisons with the Ter walvischvaart wall chart. Images of these two sources have much in common but also some important differences due to inherent variances between the Dutch source being created within an imperial metropole and the Canadian source being used in colonial outposts. The directional flow of this scholastic information—a discourse—from sender to receiver is essential to understanding how pedagogy can convey cultural meaning. Such meaning-making discourse holds an intrinsic power which, in these examples, reveals an added element of colonialism’s force. For historical educational media, a picture often remains worth a proverbial thousand words and the same can be said for these two distant but not disparate classroom objects both caught up in networks of empire and economics.

British Columbia’s (BC) New Canadian Geography textbook and Jetses’ Ter walvischvaart Dutch wall chart are contemporaneous, image-based educational media each reaching tens of thousands of reader-viewers beginning in the first decade of the twentieth-century. And because of this, each source tells modern readers much about how both Dutch and British Columbian educators conceptualized and then mediated the world for their young pupils and future citizens. During the twelve years the New Canadian Geography textbook was prescribed curriculum, the total public school enrollment grew from 23,615 annually to 50,170.[4] Even with an average attendance rate of approximately 70% it is clear that many British Columbian children were encountering this source throughout their public school experiences. This book is over 200 pages so it is not feasible to critique its entirety here, but we can sample analyse a short, five-page section titled, ‘Animals’ and also consider the importance of ‘The North’. With a critical re-reading of the New Canadian Geography that seeks to apply a decolonizing stance, a number of features emerge. These include the so-called value of animals being constrained to their utility to man and the omissive dispossession of Indigenous land.

for use in public and high schools. (British Columbia edition). (1899). W.J. Gage & Co., Ltd. https://archive.org/details/newcanadiangeogr0000onta/mode/1up?view=theater

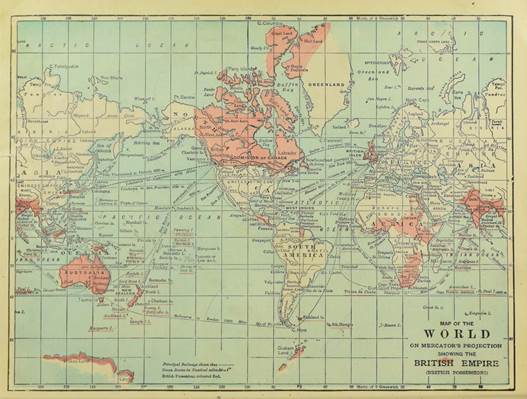

The New Canadian Geography’s tenor is persistently confident and steadily self-aggrandizing. The British Empire is central to this and particularly its properties of settler colonialism and resource extractive economies. The ‘Preface’ states from the outset that: “Geography is in reality one of the most important subjects taught in school.”[5] It goes on to claim that “[t]he illustrations are the finest ever used in any Canadian school book, and they cannot fail to give clear and definite conceptions in regard to the most important elements of true geographical study.”[6] When compared with other geography textbooks and atlases of the time, the illustrations are extensive in number and exceptional in quality. But “finest ever” is something we can never accurately know. A noteworthy part of the tone-setting preface is a sentence contextualizing the textbook’s position within an Imperial web: “The short section relating to the British Empire is of special value since the closer unity of the motherland and the colonies has become a vital question.”[7] This section appears near the end of the book and comprises five full pages starting with the empire’s ‘Extent’ which confidently states: “The British Empire, of which Canada forms so large a part, is the largest empire that has ever existed” and continues with “[t]he British Islands, which form the head of the empire and are the source from which its chief power comes, are really very small compared with the rest of the great empire which they have formed.”[8]

Next, the section goes on to contain figures of each colony’s size listed in order of total square miles beginning with Canada, followed by Australia, carrying on to twelve more colonies until ending with Jamaica. It goes on to define the British Empire by population and commerce with considerable more treatment on the later. ‘Canada’s place in the Empire’ is primarily defined by its ‘Trade Routes of the Empire’ with Canada being a central conduit for ship and rail transit with opportune commercial resources to grab along the way as one transverses the imperial globe. The British Empire’s three main types of colonial governance systems are outlined as is its overall importance worldwide. The section concludes with a direct appeal to the textbook’s young readers: “…it is on the character of each child that grows into manhood within British limits that the future of our Empire rests.”[9] For the pupils (and especially the male pupils) required to read it, this textbook served as a palpable script of imperialism, colonialism, and commercialism for the upcoming generation of citizens to perpetuate.

New Canadian Geography: Specially adapted for use in public and high schools. (British Columbia edition). (1899). W.J. Gage & Co., Ltd. https://archive.org/details/newcanadiangeogr0000onta/mode/1up?view=theater

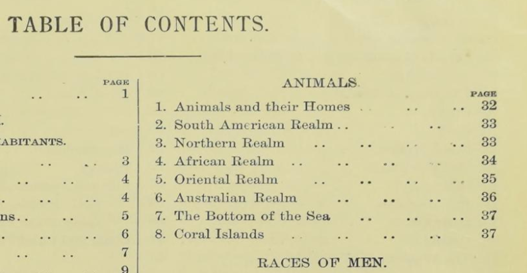

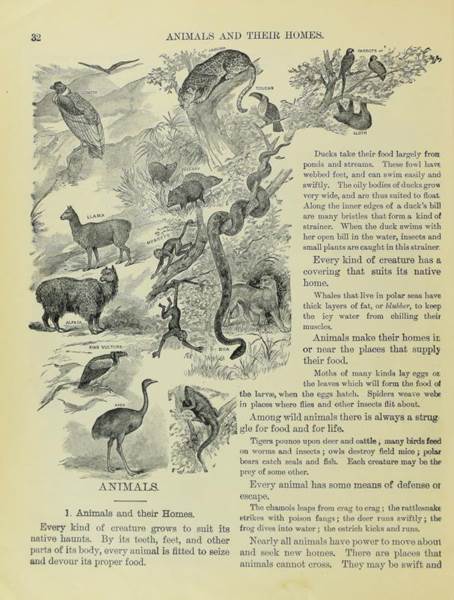

The textbook’s ‘Table of Contents’ includes a one-page introduction and a 27-page section titled ‘The Earth’ focused on physical geography. Next is a four-page section titled ‘Plants’ sub-divided into such headings as ‘Plants of the Hot Belt’ and Plants of the Northern Cold Belt’ which is very briefly stated as follows: “Northward the trees become fewer and smaller, ending with dwarf birches and willows, only a few inches in height, on the dreary plains near the Arctic shore.”[10] The next five pages are comprised of ‘Animals’ with the following eight sub-headings: ‘1. Animals and their Homes’; 2. ‘South American Realm’; 3. ‘Northern Realm’; 4. ‘African Realm’; 5. Oriental Realm’; 6. ‘Australian Realm’; 7. ‘The Bottom of the Sea’; and, 8. ‘Coral Islands’. After the section on animals comes an eleven page section titled ‘Races of Men’, a section so breathtakingly abhorrent it demands a critical and anti-racist reading in a more fulsome article on its own. Any twentieth-century reader of that section should be well-warned that it reads as a gut-wrenching guided tour of Blumenbach’s racial classification pseudo-science made genial for young readers. All subsequent sections focus on regionally distinctive descriptions equally weighted between physical and political aspects. These are divided into ‘North America’, ‘Dominion of Canada’, all the Canadian provinces that existed in 1899, ‘The United States’, ‘Central America’, ‘South America’, ‘Europe’, ‘Asia’, ‘Africa’, ‘Australia’, ‘British Empire’, ‘Review Questions’, ‘Supplement’, and ‘Maps’. The European sub-section on ‘The British Isles’ takes as many pages (17) as does both ‘Asia’ and ‘Africa’ together.

New Canadian Geography: Specially adapted for use in public and high schools. (British Columbia edition). (1899). W.J. Gage & Co., Ltd. https://archive.org/details/newcanadiangeogr0000onta/mode/1up?view=theater

Considering a close reading of the ‘Animals’ section, we find normative statements introducing most thematic paragraphs. These include ideals such as: ‘Every kind of creature grows to suit its native haunts”; “Every kind of creature has a covering that suits its native home”; “Among wild animals there is always a struggle for food and for life”; “Every animal has some means of defense or escape”; “Nearly all animals have power to move about and seek new homes”; and, “Many animals have been taken by man to new homes.”[11] Statements such as these reveal much about the mindset informing the textbook’s unspecified authors. A negative or deficit stance often dominates. Rather than animals living in an able balance with their environment, they are instead trapped within a perpetual “struggle” always needing “defense or escape.” Humans, and more specifically, “Man” actively take animals to “new homes”, for example: “Cattle, sheep, hogs and horses have been shipped from Europe across the ocean and now thrive in many parts of America.”[12] Similar sentiments continue: “Countless birds have been carried to places far from their native haunts” and “[s]heep and cattle are not native to Australia, but are now counted there in millions.”[13] Just as with masses of people caught up in the threads of imperial webs, so too are non-human animals relocated and confined to suit human purposes. Such possessive sentiments are assumed.

Through carefully constructed images and text, the child reader of this book in the early twentieth-century is presented with a curious narrative entanglement that views animals as simultaneously utilitarian within man’s dominion and also as necessary cogs in the machine of the economic productivity of the land itself. These two ideals converge directly on the notion of settler-colonialism, a concept well-articulated by Australian historian, Patrick Wolfe.[14] Wolf suggests that rather than a singular event when a so-called explorer or mercantile endeavour comes to extract and then leave again, settler colonialism is an elaborate system or structure that seeks to permanently implant itself by first dispossessing, and even eliminating, Indigenous communities and the ecological connections they exist within. With this in mind, we see clearly demonstrated how the school textbook serves as one more mechanism for the implantation of an ethos of settler colonialism not only upon the literal lands being colonized but also within the minds of the children caught up in this power-laden clamber of imperially celebrated dispossession.

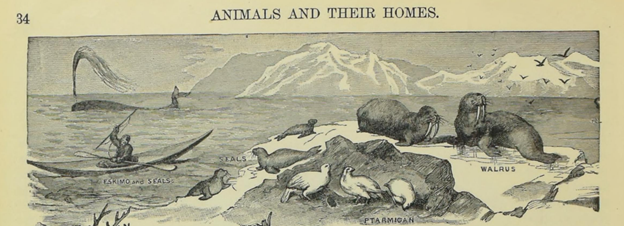

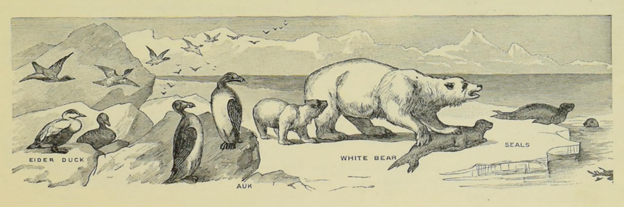

Comparing Canadian and Dutch historical education images of animals in The North

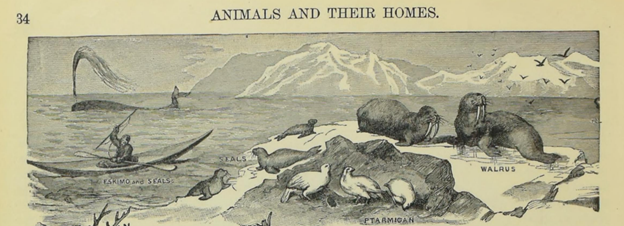

How does the New Canadian Geography relate back to Jetses’ Ter walvischvaart wall chart so well-articulated in Jacques Dane’s recent INEHC blog post? It may be constructive to begin with how the images are similar. Both are Artic scenes of ocean shores with iceberg’s in the foreground and coastline in the background. Ice, rocks, and mid-point maritime horizons frame each image, no vegetation appears in either. The New Canadian Geography comparative image is, in fact, two twined images extending a conjoined scene. Polar bears feature as protagonist animals and the bear in each image faces to the right in active attack with paws atop prey. Next, whales, walruses, and birds are also illustrated. Humans and their marine vessels are included, but here is where we observe drastically different depictions. The New Canadian Geography includes only one human, a local Indigenous person in a kayak labelled in outdated, racist language in the same line as the seals they move near. This person is depicted slightly, at a profile, and as though the individual is just one more feature of the landscape alongside the larger animals portrayed more grandly elsewhere in the image.

Jetses’ Ter walvischvaart evokes a seventeenth-century whaling voyage as a frozen moment in what can only be described as a mass slaughter. The scene could be in any polar region, such as the Nordic region, Russia, Iceland, Greenland, or what later becomes Canada; it could even be from the Antarctic. Jetses’ richly coloured wall chart is detailed with tonal shading and texture as though it were a hand-painted framed picture to enjoy for posterity. It includes seven tall ships, thirteen skips, dozens of men, and a multi-building fort. The thrust of action focuses on the harpooning or butchering of six enormous baleen whales, either Bowhead or Right. At least thirteen flags fly atop the fort or the ships and most can be made out to be the tri-coloured Dutch Statenvlag. Expressions and postures of whales and humans convey feelings of fear, physical pain, and struggle in an intense depiction of man versus animal where the polar bear serves as the only active resistor.

© Nationaal Onderwijsmuseum, Dordrecht | Noordhoff Collection | H165.962

The New Canadian Geography depicts the same landscape and animals in a much calmer scene and does so all in simple black and white line drawings from a lithograph print. While a polar bear holds a paw atop a seal, the seal is seemly disaffected by its impending attack, and instead looks elsewhere to a point of interest out of view along with all the other animals in the scene. The polar bear is accompanied by its cub making its attack of the seal a nurturing, rather than callous, act like those conveyed in Jetses’ Ter walvischvaart. The twined image of ‘Animals of the North’ on the following page includes more animals observing their surroundings from safe perches along the shore. All animals are neatly labelled: WALRUS, SEALS, PTARMIGAN, EIDER DUCK, AUK, and WHITE BEAR. A single human is depicted, a warmly-dressed person holding a spear and sitting in a kayak.[15] The image exists in a state of timelessness—it could be of imaginings of what life is like in The North when the book was printed in 1899 or it could be from 1000 years before. This source conveys a sense of chronology that is absent and seemingly irrelevant. The peaceful contrast to Ter walvischvaart’s whaling image is palpable and the trope of the noble and ecological Indigenous person known by historically by more racist names is not lost.[16]

It is here, in the seemingly bucolic scene that the hidden truth of Canada’s settler colonial forces in The North are menacing. The Dutch wall chart is starkly clear. Values of violent mercantilism and visceral non-human animal slaughter-for-profit leaves little to the imagination; capitalism is an often violent, but always necessary, aspect of so-called “progress.” Surprisingly, the Canadian textbook images of animals in the north omit everything about the very deliberate dispossession and starvation of Indigenous communities in The North that is actually occurring in these very lands at that precise time.[17] In both sources, there appears to be a deep desire to conquer the globe through economic means but also ideological ones, particularly through the tactic of categorization. When everything has a so-called clear location in an ideological taxonomy, their existence is easier to control. Vicious as it is, Jetses’ Ter walvischvaart wall chart likely depicts a scene based on historical fact. Dutch sponsored whaling expeditions did occur in polar areas during the height of Dutch economic imperialism during the seventeenth-century. Quite conversely, the New Canadian Geography demonstrates a carefully manufactured fiction that is sinister in its contrived simplicity and serenity. Through depictions of passive animals and static Indigenous identities, the Canadian example is profoundly neglectful of contemporaneous realities. By not revealing to its child readers the very violent dispossession of Indigenous lands and culture that their still emerging nation is orchestrating on their behalf, British Columbian pupils are left with a false impression of the consequences of what imperialism and settler colonialism looks like on the literal and figurative ground in Canada.

Conclusion

British Columbia’s New Canadian Geography textbook and Jetses’ Ter walvischvaart wall chart used in Dutch schools where pervasive educational tools during the early 1900s. At first glance, the visual discourses conveyed in the Dutch wall chart and the Canadian textbook are seemingly similar, both depict animals in The North through similar motifs and postures. But a closer, comparative re-reading and critical decolonizing gaze, reveal how disparate these two pedagogical devices are. How mercantile imperialism and settler colonialism are conveyed to children through images and texts differ depending on where the reader is situated on the imperial globe. According to these two sources, student reader-viewers in the metropole receive discourse messaging that prioritizes a dislocated economic extraction while those situated within the colonies are enculturated into fabricated narratives of natural peace while ignoring violent colonial realities. Analysing animals in historical educational media makes for a fruitful comparison. When these animals are located in The North, we observe how a complex constellation of power is exercised and conceptualized in a final frontier hinterland of colonial expansion in the early 1900s.

About

Pia curates the British Columbia Historical Textbooks Collection at the University of Victoria and is a member of the International Network of Educational History Collections.

Pia Russell BA MISt MEd MA (she/her)

Education Librarian—Special Collections

Doctoral Candidate—Department of History

University of Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3887-1728

Department of History profile

UVic Libraries profile

Pia’s professional blog

[1] Pia Russell is a librarian, historian, and instructor at the University of Victoria in British Columbia (BC), Canada. Chaa’winisaks is an Emerging Indigenous Scholar at Royal Roads University, also in Victoria.

[2] New Canadian Geography: Specially adapted for use in public and high schools. (British Columbia edition). (1899). W.J. Gage & Company, Limited. https://archive.org/details/newcanadiangeogr0000onta/mode/1up?view=theater

[3] New Canadian Geography: Specially adapted for use in public and high schools. (British Columbia edition). (1899). W.J. Gage & Company, Limited. Frontispiece. https://archive.org/details/newcanadiangeogr0000onta/mode/1up?view=theater

[4] British Columbia. Legislative Assembly. (1902). Thirtieth Annual Report of the Public Schools of the Province of British Columbia, 1900-1901. By the Superintendent of Education. With Appendices. http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0384208. British Columbia. Legislative Assembly. (1913). Forty-First Annual Report of the Public Schools of the Province of British Columbia, 1911-1912. By the Superintendent of Education. With Appendices. http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0059664.

[5] New Canadian Geography: Specially adapted for use in public and high schools. (British Columbia edition). (1899). W.J. Gage & Company, Limited. Preface, page 1. https://archive.org/details/newcanadiangeogr0000onta/mode/1up?view=theater

[6] New Canadian Geography: Specially adapted for use in public and high schools. (British Columbia edition). (1899). W.J. Gage & Company, Limited. Preface, page 2. https://archive.org/details/newcanadiangeogr0000onta/mode/1up?view=theater

[7] New Canadian Geography: Specially adapted for use in public and high schools. (British Columbia edition). (1899). W.J. Gage & Company, Limited. Preface, page 2. https://archive.org/details/newcanadiangeogr0000onta/mode/1up?view=theater

[8] New Canadian Geography: Specially adapted for use in public and high schools. (British Columbia edition). (1899). W.J. Gage & Company, Limited. Preface, page 205. https://archive.org/details/newcanadiangeogr0000onta/mode/1up?view=theater

[9] New Canadian Geography: Specially adapted for use in public and high schools. (British Columbia edition). (1899). W.J. Gage & Company, Limited. Preface, page 209. https://archive.org/details/newcanadiangeogr0000onta/mode/1up?view=theater

[10] New Canadian Geography: Specially adapted for use in public and high schools. (British Columbia edition). (1899). W.J. Gage & Company, Limited. Preface, page 31. https://archive.org/details/newcanadiangeogr0000onta/mode/1up?view=theater

[11] New Canadian Geography: Specially adapted for use in public and high schools. (British Columbia edition). (1899). W.J. Gage & Company, Limited. Preface, pages 32-33. https://archive.org/details/newcanadiangeogr0000onta/mode/1up?view=theater

[12] New Canadian Geography: Specially adapted for use in public and high schools. (British Columbia edition). (1899). W.J. Gage & Company, Limited. Preface, pages 33. https://archive.org/details/newcanadiangeogr0000onta/mode/1up?view=theater

[13] New Canadian Geography: Specially adapted for use in public and high schools. (British Columbia edition). (1899). W.J. Gage & Company, Limited. Preface, pages 33 and 36. https://archive.org/details/newcanadiangeogr0000onta/mode/1up?view=theater

[14] Wolfe, Patrick (2006). ‘Settler colonialism and the elimination of the native,’ Journal of Genocide Research, 8:4, 387-409, http://10.1080/14623520601056240.

[15] New Canadian Geography: Specially adapted for use in public and high schools. (British Columbia edition). (1899). W.J. Gage & Company, Limited. Preface, pages 33 and 34. https://archive.org/details/newcanadiangeogr0000onta/mode/1up?view=theater

[16] Gin Lum, K. (2022). Heathen: Religion and Race in American History. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674275782

[17] Gombay, N. (2024). Food security and the ma(s)king of indigenous peoples’ dispossession: the example of Inuit in Canada. Social & Cultural Geography, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2024.2399238